For decades, the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease has relied on a combination of cognitive assessments, brain imaging, and sometimes invasive procedures like spinal taps. But what if the eyes—often called the window to the soul—could also serve as a window to the brain? Recent breakthroughs in neuroscience suggest that subtle changes in eye movement patterns may hold the key to detecting Alzheimer’s disease long before memory lapses become apparent. This discovery could revolutionize early intervention strategies, offering hope for millions at risk of this devastating condition.

The Science Behind the Link

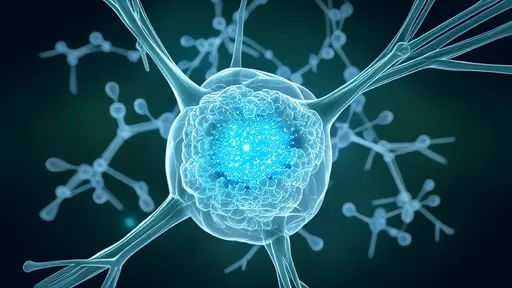

Researchers have long observed that Alzheimer’s doesn’t just affect memory—it disrupts a wide range of neural pathways, including those governing visual processing and eye movements. The retina, an extension of the central nervous system, shares many biological features with the brain. When amyloid plaques and tau tangles begin to accumulate in the brain, they also appear in retinal tissue. This parallel degeneration manifests in measurable ways, such as delayed pupil responses, impaired smooth pursuit eye movements, and erratic fixation patterns during visual tasks.

Studies using high-speed eye-tracking technology have revealed that individuals with preclinical Alzheimer’s exhibit distinct oculomotor signatures. For example, they struggle with “anti-saccade” tests, which require suppressing the instinct to look at a suddenly appearing visual target. Healthy adults can typically perform this task with ease, but those with early neurodegeneration show hesitation and errors. These findings suggest that eye movement analysis could serve as a non-invasive, cost-effective biomarker for Alzheimer’s pathology.

From Labs to Clinics: The Diagnostic Potential

One of the most promising aspects of this research is its scalability. Unlike PET scans or cerebrospinal fluid analysis, eye-tracking devices are portable and require minimal training to operate. A 2023 study published in Nature Aging demonstrated that a 10-minute eye movement test could distinguish between healthy older adults and those with amyloid positivity at 85% accuracy. Such tools could eventually be deployed in primary care settings, enabling widespread screening for at-risk populations.

Moreover, certain eye movement abnormalities appear years before clinical symptoms. A longitudinal study tracking individuals with genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s found that subtle oculomotor changes preceded cognitive decline by up to a decade. This early warning system could be invaluable for enrolling patients in clinical trials for disease-modifying therapies at stages when interventions might be most effective.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Despite its promise, the approach isn’t without limitations. Not all eye movement alterations are specific to Alzheimer’s—conditions like Parkinson’s or even normal aging can produce similar patterns. Researchers are refining algorithms to improve specificity by combining eye-tracking data with other biomarkers. There’s also the delicate question of how to communicate risk to asymptomatic individuals, given the current lack of curative treatments.

Ethically, the advent of accessible predictive testing raises concerns about psychological distress and insurance discrimination. Advocates emphasize the need for robust counseling frameworks alongside any future eye-based diagnostics. “We must ensure that earlier detection translates to meaningful support, not just earlier anxiety,” notes Dr. Elena Torres, a neuroethicist at Columbia University.

The Road Ahead

Several biotech startups are already commercializing eye-tracking systems for neurodegenerative disease assessment. Meanwhile, large-scale trials like the U.S.-based “EyeRemember” study aim to validate these techniques across diverse populations. If successful, routine eye movement screenings could become as standard as blood pressure checks for older adults.

This research also opens new avenues for monitoring treatment efficacy. Since eye movements can be measured repeatedly without risk, they may help track whether experimental therapies slow neurodegeneration in real time. Some teams are even exploring whether visual training exercises could strengthen vulnerable neural circuits as a preventive measure.

As the global population ages, the urgency for accessible Alzheimer’s diagnostics has never been greater. While more work lies ahead, the marriage of neuroscience and ophthalmology offers a glimpse of a future where a simple eye test could safeguard one of humanity’s most precious faculties—memory itself.

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025