In a groundbreaking development that could reshape quantum communication networks, researchers have demonstrated the first successful implementation of solid-state lattice trapping for photonic quantum memory. This technique, often referred to as "optical pulse imprisonment," enables the storage and retrieval of fragile quantum information carried by light pulses within crystalline structures at room temperature. The achievement marks a significant leap toward practical quantum repeaters and long-distance quantum communication systems.

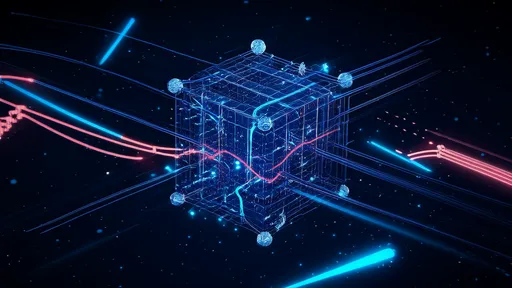

The core innovation lies in engineering special defects within diamond crystals that create an "energy landscape" capable of capturing and holding photons. Unlike conventional quantum memory approaches requiring cryogenic temperatures, this solid-state method operates under everyday conditions. Scientists achieved this by precisely manipulating nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond lattices, creating what they describe as "optical traps" for photon storage.

What makes this discovery particularly remarkable is the storage duration. Previous attempts at room-temperature quantum memory typically maintained photonic states for nanoseconds before decoherence occurred. The new technique extends this to milliseconds - an eternity in quantum terms - while preserving the delicate quantum properties of the trapped light. This duration allows sufficient time for processing quantum information or relaying it through network nodes.

The experimental setup involves firing precisely calibrated laser pulses into the engineered diamond crystal. When photons enter specific lattice sites, their energy gets redistributed among surrounding atoms, effectively freezing the light pulse in place. A subsequent control pulse can later release the stored photons with their quantum information intact. Researchers compared the process to "hitting pause on a light beam, then resuming playback without quality loss."

Practical applications already appear on the horizon. Quantum networks require memory nodes to compensate for photon loss during transmission. Current fiber-optic quantum communication suffers from a 50% signal loss every 15-20 kilometers. This new storage method could enable quantum repeaters that capture and retransmit signals, potentially enabling continental-scale quantum networks without requiring impractical numbers of entangled photon sources.

Beyond communications, the technology shows promise for quantum computing. Photonic quantum processors could utilize these memory units as temporary storage registers during complex calculations. The solid-state nature makes integration with existing chip manufacturing techniques theoretically possible, though significant engineering challenges remain regarding scalability and defect control.

Several research groups worldwide have begun replicating and expanding upon these initial results. Early attempts focus on increasing storage density by engineering crystals with multiple independent trapping sites. Others work on improving retrieval efficiency - currently at about 60% - to make the technology viable for commercial applications. The race is on to develop the first prototype quantum repeater using this approach within the next three years.

While celebrating this advancement, scientists caution that significant hurdles remain before widespread deployment. The precision required in crystal engineering currently makes mass production challenging. Additionally, the method works best with specific photon wavelengths used in quantum communication, requiring adaptation for broader applications. Nevertheless, the scientific community agrees this represents the most promising path toward practical quantum memory solutions to date.

Funding agencies and tech companies have taken note. Major investments are flowing into related research, with both government and private sectors recognizing the technology's potential to unlock the next generation of secure communications. As one lead researcher stated, "We're no longer just trapping individual photons - we're capturing the building blocks of the quantum internet." The coming years will reveal whether this crystalline approach can indeed provide the missing link for global quantum networks.

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025